How the war in Libya is fought without weapons

From workshop to battlefield

No signs marked the entrance to the Mad Max weapons factory on the outskirts of Misrata; it was just an old garage with bare concrete walls. A bookshelf full of manuals for farm equipment stood near the door of the cavernous hall, serving as dusty reminders of better days, when mechanics focused their energies on maintaining a well oiled agricultural economy around the flourishing coastal city. In the summer of 2011, however, the civil war transformed every-thing.

Farms around Misrata turned into tactical terrain where troops loyal to Colonel Moammar Gadhafi fought pitched battles against ragged volunteers from the rebellious city. Rolling dunes on the city outskirts became sand bunkers. Scenic highways along the Mediterranean served as strate-gic corridors. The city itself looked like a Hollywood set when I visited in August, with so many burned cars and walls scarred by explosions that it seemed a figment of an overzealous imagination, some dark and twisted vision of a post-apocalyptic landscape.

Mechanics who once tended to farming equipment now modify guns and build aggressive “technical” trucks. Mechanics who once tended to farming equipment now modify guns and build aggressive “technical” trucks.

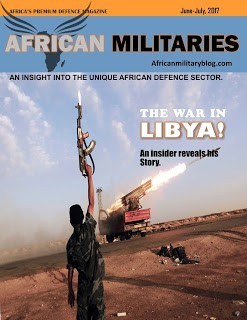

An equally bizarre collection of vehicles roared along the ruined streets, like products of a science fiction universe with their homemade paint jobs and jury-rigged armor. These were the re-bels’ battle wagons, usually pickup trucks some kind of artillery welded to the back.

This crazy species of fighting vehicle evolved from the light gun trucks that played an important role in dozens of African wars, fought across vast distances by small groups of men with modest budgets. The Somalis made the “technical”, a type of improvised fighting vehicle, famous in the 1990s. But many other armies throughout the continent’s history have discovered that fast, agile forces can beat stronger, slower opponents.

Desert wars are sandstorms, blowing in with tremendous speed and ferocity. The Libyan war was no exception: when you’re not sure whether the front lines are 300 kilometres away or just over the next ridge; when you’re not entirely clear about what your friends are doing and even less sure about your enemies, you really want to feel some oomph under your gas pedal.

I followed one of the battle wagons to the garage to see the place where this species of homemade fighting vehicles was assembled and repaired. Despite the lack of signage, the spot was easy to find because of the loud bursts of automatic gunfire coming from the shop’s test range.

Fighters gathered there in the evenings after days of battle under the blazing sun, telling stories and hammering their broken weapons back into service.

The rebels were badly outgunned but compensated with wicked creativity. They fashioned shotguns from steel pipes and drilled out the bores of starter pistols to make handguns. They ransacked a military airfield and stripped the weaponry from old Russian fighter jets, then reinforced the chassis of pickup trucks to handle the groaning weight of aircraft guns.

One particularly gifted welder even built his own troop carrier, layering steel plates around a Chinese pickup truck, but the behemoth went into retirement as soon as the fighting broke away from the block-by-block grind in the city center and the rebels needed faster vehicles for the surrounding countryside.

Some of these modifications seemed unnecessarily theatrical—in a war fought with 14.5-millimeter machine guns, how often do you need a battering ram?—and the mechanics would sheepishly admit that they added a few flourishes for the sake of intimidation. Many of them had watched the Mad Max movies and would discuss the merits and drawbacks of the military hardware used by Mel Gibson’s character in the series.

These were not lighthearted conversations, however. The mechanics of Misrata went about their work with a grim seriousness, a profound desire to get back to repairing farm equipment someday, much later, when the killing would end.

Sadiq Mubakar Krain's blue overalls are soaked with sweat as he works on an improvised rocket launcher for the rebels fighting Muammar Gaddafi.

"This is the first time I make one of these," said Krain, 52, pointing to a launcher that consists of 16 rocket tubes scavenged from a military helicopter.

A bespectacled former foreman at an oil company, Krain has fixed the tubes in a welded frame and is working on the electronics that will allow rebel fighters to fire individual rockets at will.

"I have learned to make other things and to weld, so God willing, I have got this one right," Krain said at workshop where he and his colleagues build weapons out of whatever they can lay their hands on.

The ingenuity on display is a product of necessity. The Misrata rebels have captured some weapons and others are shipped to them via the city's port.

But heavy arms are in short supply and those the rebels have obtained need to be adapted to match the firepower and mobility of the government forces they are fighting.

The rebels in Misrata, Libya's third largest city about 200 km (130 miles) east of Tripoli, have been fighting for the past four months to end Gaddafi's 41-year rule.

They have moved the front line from inside this city to the outskirts of Zlitan, a neighboring town now blocking the rebels' advance toward Tripoli.

The intense pace of the workers in this shop near the center of Misrata -- who include former teachers, engineers and a truck driver -- suggests the rebels are preparing the muni-tions for the next push toward Zlitan.

Mend and Make Do

Until now, the workshop has been focused on repairing equipment. When the front line moved forward last week, most of the workers here were transferred to a new repair shop closer to Zlitan so that gun crews did not have to drive 36 km (20 miles) each way to have their weapons fixed.

The shop in Misrata still handles major repairs, but is now concentrating on preparing new weapons and the trucks on which to mount them. The pace is intense -- work goes on from early in the morning to late at night seven days a week.

The main job is to build new housings for heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft guns that will be mounted on the back of pickup trucks. The weapons are placed facing backwards so the vehicles reverse into position to open fire.

There are about 10 new welded steel mounts nearly ready for 14.5 mm machine guns taken from tanks or helicopters to be attached, while one is ready to go.

Instead of an electronic system to move it, the gun can be adjusted manually up and down or side to side. The trigger works using the brake line from a small car and there is a rudimentary safety catch.

Loading Bullets

Salah Mohammed, 45, proudly shows off the new gun, plus a homemade round for it made using used scavenged cas-ings.

The workshop has also devised a basic welded tool with a handle to push the rounds into the links that will feed the ammunition into the machine gun, something that cannot be done by hand.

"One press of the trigger," Mohammed says, pressing the trigger for a second to demonstrate, "is nine bullets." "So we need many bullets."

In the corner, workers attach steel plates to an ancient pickup truck. Mohammed, a former engineer at an oil com-pany, says the truck was an old wreck but its engine has been rebuilt.

By far the most feverish activity among the 35 workers in the workshop is centered on a small group working to fin-ish rebuilding an anti-aircraft gun.

The workers have stripped the gun, which has a seat for the gunner, of its four 14.5 mm machine guns and replaced them with two 23 mm anti-aircraft guns.

Krain says the change of caliber is partly because the bigger guns have a range of 6 km compared with the 4 km of the 14.5 mm guns.

But he says it also because the gun has a psychological impact on the pro-Gaddafi troops.

"When they hear the sound the gun makes," he pauses to make a long, deep 'doof, doof, doof' sound to mimic the gun, "they run away."

Krain, his hands coated in oil, returns to work on his rocket launcher.

"I want to help finish the war by Ramadan," he says. Ramadan, the Muslim holy month of fasting and prayer, starts in early August.

"Our work will not be over then, we have much to do. But I want the fighting to stop by then."

This article first appeared in the edition of African Militaries Magazine. you can download it here